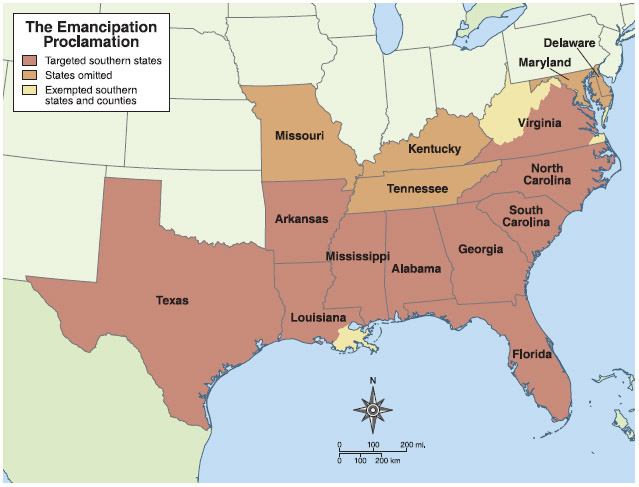

The Emancipation Proclamation only applied to the states in rebellion.

President Lincoln justified the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure intended to cripple the Confederacy. Being careful to respect the limits of his authority, Lincoln applied the Emancipation Proclamation only to the Southern states in rebellion.

Of the states that were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, and West Virginia prohibited slavery before the war ended. In 1863, President Lincoln proposed a moderate plan for the Reconstruction of the captured Confederate States of Louisiana. Only 10% of the electors in the state were required to swear the loyalty oath. Additionally, the Proclamation had to be ratified and slavery had to be outlawed in the state's new constitution. By December 1864, the Lincoln plan abolishing slavery had been enacted not only in Louisiana but also in Arkansas and Tennessee. In Kentucky, Union Army commanders relied on the Proclamation's offer of freedom to slaves who enrolled in the Army and provided freedom for an enrollee's entire family; for this and other reasons, the number of slaves in the state fell by more than 70 percent during the war. However, in Delaware and Kentucky, slavery continued to be legal until December 18, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment went into effect.

Therefore, the Emancipation Proclamation did not free all slaves in the US, contrary to a common misconception; the Proclamation applied in the ten states that were still in rebellion in 1863, and thus did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slave-holding border states that had not seceded. Those slaves were freed by later separate state and federal actions.