Top 6 Ancient Mesopotamia Social Classes

Mesopotamia is a historical region of Western Asia located in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent along the Tigris-Euphrates river system. Mesopotamia ... read more...now occupies modern Iraq. In a larger sense, the historical territory includes modern-day Iraq and Kuwait, as well as parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey. The Sumerians and Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians) governed Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was captured by the Achaemenid Empire. It was conquered by Alexander the Great in 332 BC and became part of the Greek Seleucid Empire following his death. Later, the Arameans ruled over much of Mesopotamia (c. 900 BC - 270 AD). Here are the top 6 ancient Mesopotamia social classes.

-

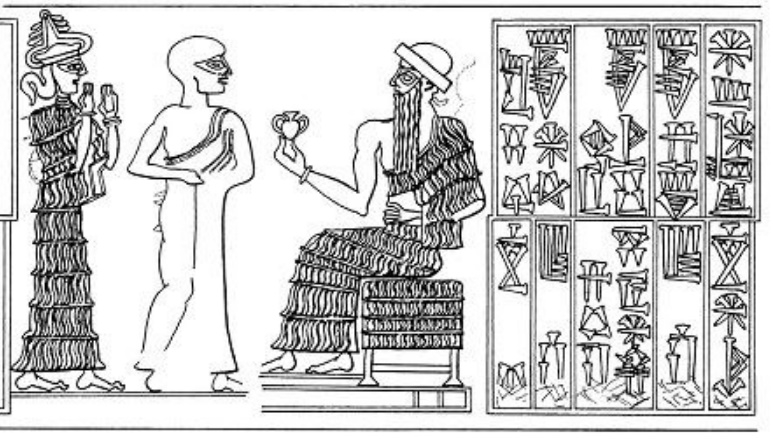

The first class in our list of ancient Mesopotamia social classes we want to introduce to you is the King and the nobility. According to Richard Marrison, kings had direct interaction with the gods and operated as a bridge between humans and gods. Any King's strength was determined by the overall area of the territory he was able to conquer. The larger the domain, the greater his power. Sargon of Akkad was the most powerful ruler of an ancient civilization. He established himself as the most influential King through military conquests and Empire expansion.

The Mesopotamians thought their kings and queens were derived from the City of Gods, but, unlike the ancient Egyptians, they never considered their kings to be true gods. The majority of kings referred to themselves as "king of the universe" or "great king." As rulers had to look after their subjects, another prevalent moniker was "shepherd."

This category included, in addition to the King, the King's family, and the nobles. The nobility was in charge of the city-state, region, or Empire. They were also granted rights comparable to those of royalty. This category's burials were elaborate, with an opulent burial tomb. They were also given personal diviners to interpret the unseen message and predict the future using supernatural skills.

Bronze head of a king, perhaps Sargon of Akkad, from Nineveh (now in Iraq), Akkadian period, c. 2300 BCE; in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad -britannica.com

worldhistory.org -

Priests were at the top of the social pyramid because they were the closest to the gods that Mesopotamia believed in. In fact, they were the only people permitted to enter a ziggurat! The ziggurat stood in the heart of each city-state. The monks lived nearby in two-story sun-hardened mud brick dwellings. In Mesopotamia, a priest was in charge of ensuring that everyone behaved in a way that pleased the gods.

The training to become a priest or priestess, according to John Patrick Guinto, was long and tough, but the benefits were immense. Priests generally served a male god and priestesses a goddess, while some priestesses worked in male god temples. In Mesopotamia, priestesses were the first dentists and doctors.

Enhenduanna, the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, was the most famous priestess of ancient Mesopotamia. In the time of her father, Sargon of Akkad, Enheduanna was the EN priestess of the moon deity Nanna in the Sumerian city-state of Ur. Her father most likely designated her as the leader of the religious cult at Ur in order to strengthen relations between her father's Akkadian religion and the native Sumerian religion. Enheduanna has been hailed as the world's first named author, with a number of works in Sumerian literature, such as the Exaltation of Inanna, including her as the first-person narrator, and other works, such as the Sumerian Temple Hymns, perhaps identifying her as the author.

A Mesopotamian ziggurat -surfiran.com

Enheduanna -en.wikipedia.org -

The third class in our list of ancient Mesopotamia social classes is Scribe. Scribes were among the most educated people in the world around 2000 B.C. Scribes gradually developed skills in math, science, business, and literature, in addition to reading and writing cuneiform. They were elevated to the upper class because of these attributes, as well as their service to the King. They were the teachers, teaching everyone how to write and read. They also worked in temples, at court, and as royal tutors.

In reality, 70% of the scribes recognized by name were the sons of society's upper crust, including royalty. This isn't to argue that status was a prerequisite for becoming a scribe, but rather the normal source of the prerequisite: money. The son of a merchant has the same chance as the son of a monarch of becoming a scribe. Even more socially progressive, the daughter of a monarch finally had the same chance of becoming a scribe as her male equivalent.

"The scribe did not so much read a line of text as translate it", stated Jerald Starr on his website. In order for a scribe's basic literacy abilities to be useful, he or she had to learn commerce, arithmetic, science, and literature. In other words, scribes needed to understand the context of what they were reading in order to read it. This is because cuneiform, a system used to record several languages, was phonetic, one syllable could make up any number of words, with any number of definitions, depending on whether you were writing in Sumerian or another Mesopotamian language.

allmesopotamia.wordpress.com

-

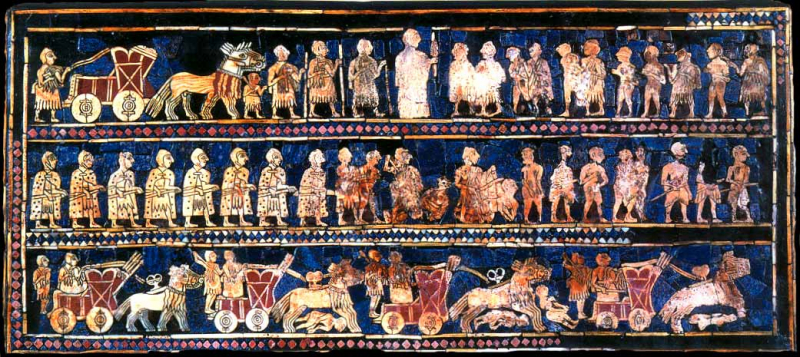

Mesopotamia trade grew organically from the crossroads nature of the civilizations that dwelt between the rivers and the fertility of the land, according to History on the Net. Because of irrigation, southern Mesopotamia was abundant in agricultural products such as fruits and vegetables, nuts, dairy, fish, and meat from both wild and domestic animals. Aside from food, Mesopotamia was rich in mud, clay, and reeds, which they used to build their cities. Mesopotamia was required to trade for the majority of other essential goods, such as metal ores and timber. Long-distance trade was required for resources like copper and tin, as well as luxury items for the nobility, in addition to local trade, which brought food and animals into the city and took tools, plows, and harnesses out to the countryside. Early Mesopotamian merchants and traders formed caravans for long-distance trading.

Mesopotamian craftsmen produced a wide range of trade goods, including beautiful fabrics, robust, practically mass-produced ceramics made in temple workshops, leather goods, jewelry, basketry, devotional figurines, and ivory carvings, among others. Agricultural products such as grains and cooking oils, as well as dates and flax, were also exported.

Merchants established trade emporiums in different regions and cities as Mesopotamian trade expanded. Assyrian traders established a trading outpost in Kanesh, Anatolia, around 1700 B.C. The merchants journeyed nearly 1,000 miles to this city in modern-day Turkey. The Assyrian merchants paid a levy to the city's ruler to live in Kanesh and trade with the city dwellers and other merchants who traveled from afar to trade for Mesopotamian items.

historyonthenet.com

history.com -

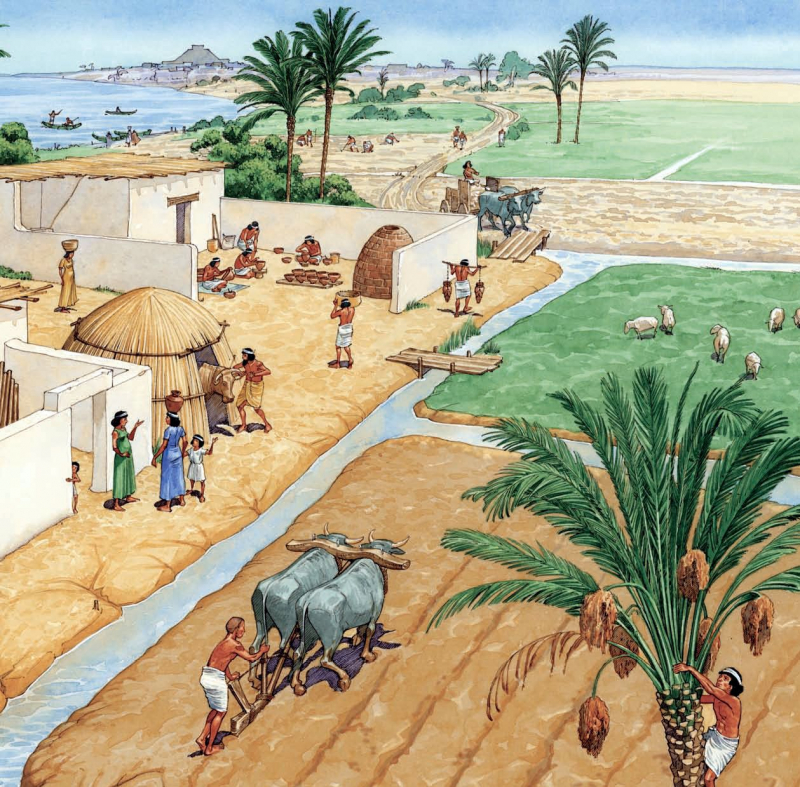

According to Richard Marrison, this class primarily consisted of working-class individuals such as farmers, musicians, builders, artisans, carpenters, prostitutes, and butchers. These people were the ones who kept the city running by going about their daily lives. Everyone had varied responsibilities that made their lives easier.

Artisans, for example, played important roles in this civilization's culture since they were highly qualified and made items that were necessary for their everyday lives. Pots, cloths, weapons, baskets, dishes, and works of art worthy of pleasing gods were among the creations.

The majority of the population (about 80%) was a farmer, therefore they spent their time outside the city walls, in the fertile fields, farming crops like barley, wheat, flax, onions, figs, grapes, and turnips. These people resided in one-story mud-brick dwellings the furthest away from the ziggurat. Under the supervision of the institutions that dominated the economy: the royal and provincial palaces, the temples, and the domains of the elites, Mesopotamian farmers developed effective strategies that enabled them to support the development of the first states, first cities, and then the first known empires. They mostly farmed cereals (especially barley) and livestock, although they also farmed legumes, date palms in the south, and grapes in the north.

ancienthistorylists.com

pinterest.fr -

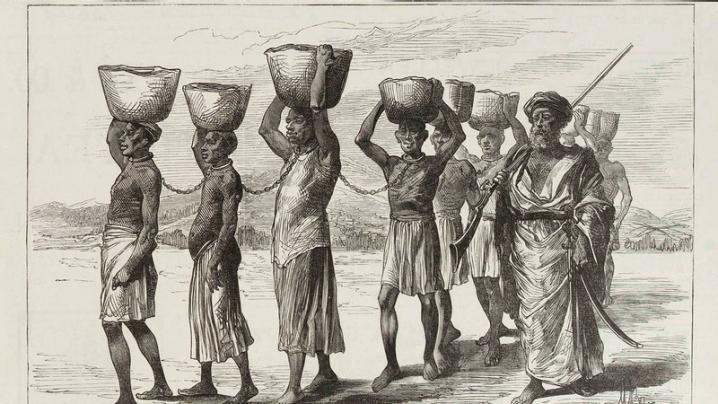

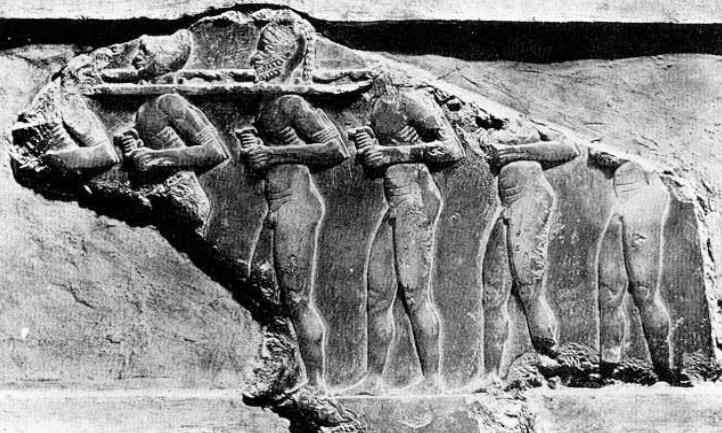

Slaves belonged to the lowest class in the ancient Mesopotamia social classes, at the bottom of the social class pyramid. People in the lowest class were punished by the nation, kidnapped, trafficked, sold themselves because they couldn't pay off debt, and sold by their relatives to settle the debt. According to John Patrick Guinto, crimes like harming one's elder brother or mother were punished by enslavement. As a result, slaves were mostly procured from war captives and criminals. Slaves were forced to wear textile skirts fastened around their waists and extending up to their knees and as long as the owner so desired.

Slavery was widespread and popular in ancient cultures, and it was especially common in Mesopotamian society. The society recognized for its accomplishments in many aspects of life was essentially a primitive, semi-barbarian civilization. Slavery existed and was prevalent across Mesopotamia.

According to Richard Marrison, despite the fact that members in this class were well prepared, skilled, and talented, they were never given the opportunity to advance to higher grades. They were not given the same rights or power as the upper class. They were tasked with instructing youngsters, caring for horses, managing accounts, crafting jewelry, and creating a variety of artworks. Almost everyone was capable and efficient enough to finish the allocated chores in the time allotted.

aboutmesopotamia.weebly.com

histclo.com