Top 7 Interesting Facts About John Dalton

John Dalton was a British scientist who is most known for his contribution to the atomic hypothesis, which is the basis of contemporary chemistry. Dalton began ... read more...working as a teacher at the age of 12 and completed much of his education while teaching. He was born into a Quaker family of limited means. Before becoming one of the most influential chemists of all time, he began his professional career as a meteorologist, making several significant discoveries in the discipline. Today, let's follow Toplist to discover some interesting facts about John Dalton.

-

John Dalton was born on September 6, 1766, in the English village of Eaglesfield, in the county of Cumberland. Jonathan Dalton, his grandpa, was a shoemaker, and his father, Joseph Dalton, was a weaver. His early education was provided by his father and Quaker John Fletcher, who conducted a private school in Pardshaw Hall, a nearby village. Quakers were Christians who opposed the established Church of England and believed in the priesthood of all believers, among other things. Joseph Dalton, John's father, was a Quaker. In 1755, Joseph married John's mother, Deborah Greenup, a Quaker who came from a landowning family.

Dalton was never married and has a small circle of pals. He led a simple and quiet personal life as a Quaker. Dalton lived in a room in the home of the Rev W. Johns, a noted botanist, and his wife in George Street, Manchester, during the 26 years leading up to his death. In the same year, Dalton and Johns died (1844).

Only annual trips to the Lake District and occasional trips to London gave Dalton a break from his daily routine of laboratory work and instructing in Manchester. In 1822, he paid a brief visit to Paris, where he met a number of notable local scientists. He attended several of the British Association's earlier meetings in York, Oxford, Dublin, and Bristol.

Photo: aboutmanchester

Photo: rsc.org -

Dalton was a Christian who also happened to be a Quaker. Members of the Quaker movements believe that their ideals and the ability to access the light within each human being bind them all together. Dalton had to go to Kendal, roughly 45 miles from his family's home, when he was 15 years old in order to attend a Quaker school. He truly wanted to be a lawyer or a doctor after finishing his education, but he couldn't since he was a Dissenter. John Dalton’s religion was truly important to him.

Individuals or households who practiced a different faith in the United Kingdom were known as Dissenters. Being a Dissenter meant being excluded from many activities, including attending English universities, at a time when the Church of England had a significant impact on everyone's lives. Dalton began teaching at the Quaker school where he had previously studied and excelled. He became the school's principal after four years.

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org

Photo: istmira -

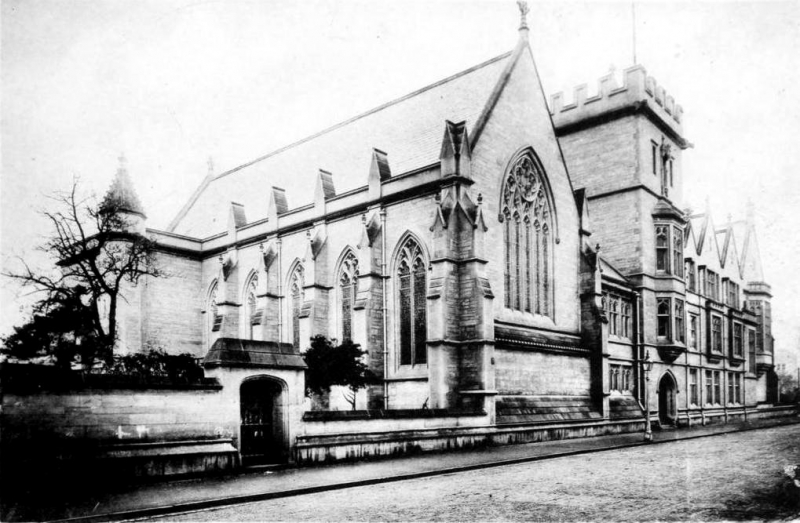

John Dalton and his brother opened a Quaker school in Kendal when they were 15 years old, teaching roughly 60 students. He became principal of the school when he was 19 years old and remained in that position until he was 26 years old. One of the interesting facts about John Dalton is he traveled to Manchester in 1793, when he was 27 years old, to teach mathematics and natural philosophy at the New College, a dissenting academy. He was appointed as a math and natural philosophy teacher.

Dalton spent a lot of time at his makeshift laboratory on George Street, which was the headquarters of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. He investigated and weighed gases he gathered from a pond near Old Trafford while he was there. He wondered aloud how water vapor and oxygen could coexist in the same area. They have to be made up of separate particles. Dalton developed his innovative atomic theory in 1803, based on this fundamental premise, which stated that all substance is made up of atoms. Unfortunately, his notes were destroyed when the building was bombed during WWII.

Dalton's calculations benefited researchers for the large Manchester cotton manufacturers in his day, and they were quickly developing new hues based on his chemical discoveries. Manchester was put on the map of the modern world by John Dalton. In the early nineteenth century, his scientific discoveries changed an industry in which Manchester was the world leader, affected an important field of anatomy, and pioneered our understanding of weather.

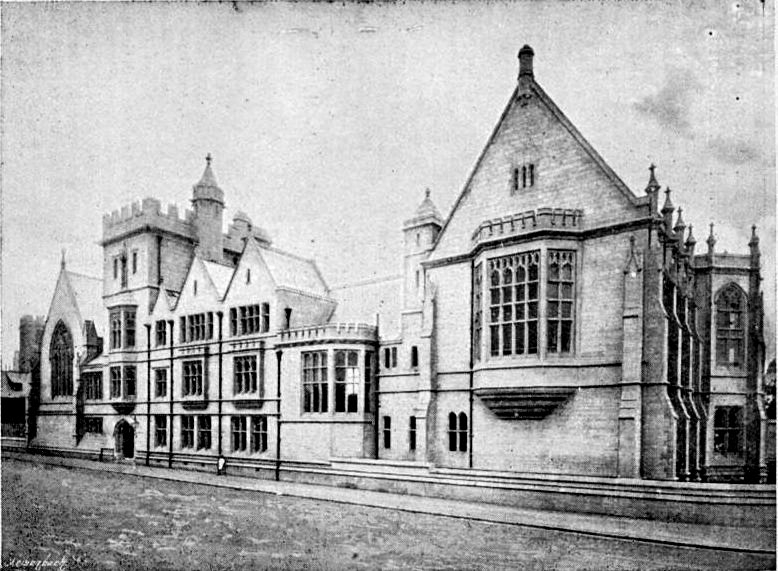

Photo: victorianweb

Photo: victorianweb -

Dalton grew up in an impoverished home and had to work from the time he was a child to support himself. Because he was a Church of England Dissenter, his educational prospects were similarly limited. The first notable mentor who contributed to Dalton's education was Elihu Robinson, a wealthy Quaker gentleman with scientific accomplishments whom Dalton met when he was 10 years old. With Elihu Robinson, a "gentleman of property" in the area, Dalton began studying mathematics and collecting meteorological data.

Dalton moved to the nearby town of Kendal with his older brother Jonathan to work as an assistant at a boarding school operated by their cousin George Bewley when he was fifteen. Bewley retired and sold the school to the Dalton brothers, who ran it for the following twelve years. Dalton met his second key instructor, John Gough, at Kendal. Dalton's pursuit of scientific inquiry was encouraged by Gough, who had been blind since boyhood, and he assisted him in developing his habit of empirical inquiry into the issues that affected him. On the advice of Mr. Gough, Dalton travelled to Manchester, England, in 1793 to work as a tutor in mathematics and natural philosophy (science) at the New College there. He was carrying the manuscript of his first book, Meteorological Observations and Essays, which he had dedicated to Mr. Gough. Dalton's daily meteorological observations, which he kept up until the day before his death, were the basis for the book, which was published in 1798.

Both of these mentors sparked an interest in meteorology in Dalton that lasted the rest of his life. John learned the fundamentals of mathematics, Greek, and Latin from these men. Dalton learned practical knowledge in the building and use of meteorologic instruments, as well as how to preserve daily weather records, from Robinson and Gough, who were also amateur meteorologists in the Lake District. For the remainder of his life, Dalton was fascinated by meteorological measurements.

Photo: happyhappybirthday

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org -

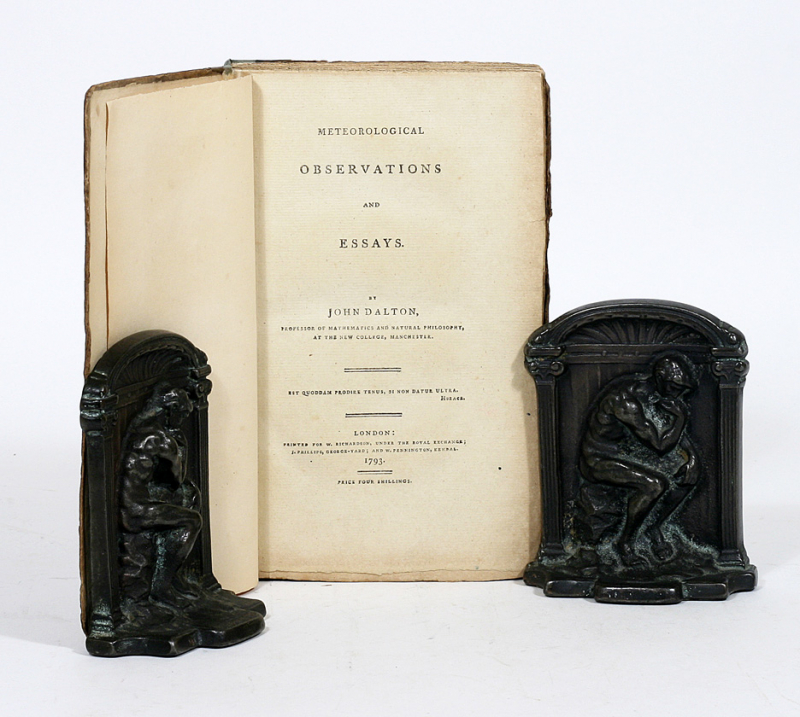

Robinson and Gough, two of Dalton's most influential teachers, were amateur meteorologists who sparked John Dalton's interest in meteorology, the scientific study of the atmosphere. In 1787, Dalton began keeping a meteorological notebook, in which he recorded almost 200,000 observations over the next 57 years. At the age of 27, Dalton published his first publication, Meteorological Observations and Essays, in 1793. Despite the fact that it received little attention, it offered insightful observations and novel concepts.

Dalton's daily meteorological observations were the basis for the book, which he kept up until the day before his death. The book was one of the first of its sort, and it helped to establish meteorology as a legitimate scientific study, earning Dalton the title of "Father of Meteorology" from John Frederic Daniell, a contemporary of Dalton's. Dalton's very personal reliance on his own empirical investigation was also highlighted in the book. "Having been so often misled in my progress by taking for granted the results of others, I have determined to write as little as possible but that I can attest by my own experience," he wrote, “having been in my progress so often misled by taking for granted the results of others, I have determined to write as little as possible but that I can attest by my own experience.”

Photo: manhattanrarebooks

Photo: milestone -

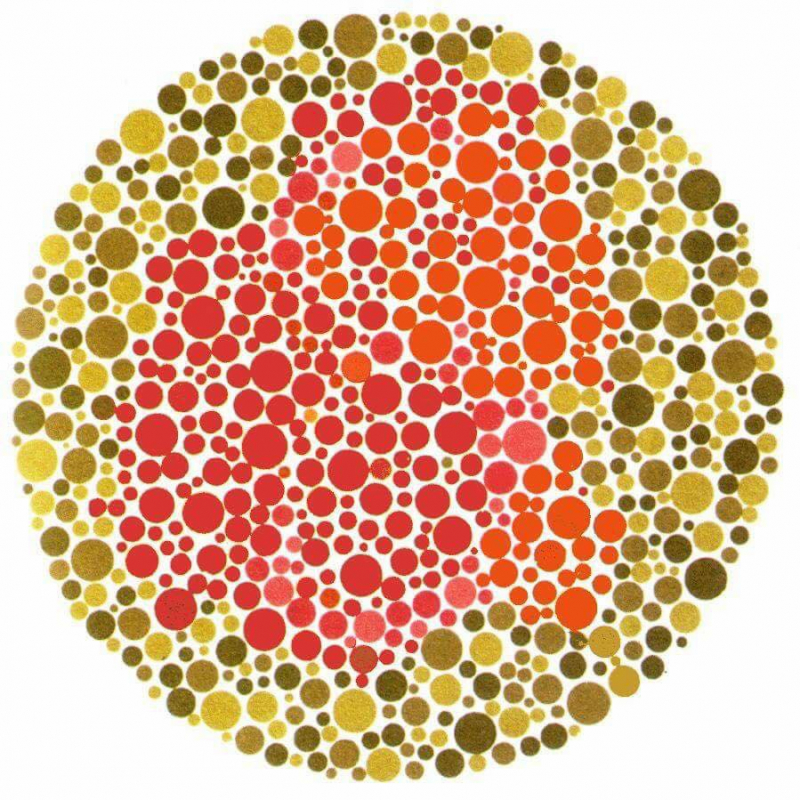

Dalton was elected a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society on October 3, 1794, when he was 28 years old. For the first time, Dalton had access to a laboratory as a member of the organization. One of the interesting facts about John Dalton is he contributed his first paper, "Extraordinary facts relative to the vision of colors," shortly after joining the organization, which documented the flaw he had identified in his own and his brother's vision. Both John and Jonathan Dalton have "color deficiency" or the inability to distinguish some colors in visual stimulation (complete color blindness or monochrome is exceedingly rare). Color blindness can be caused by a genetic mutation in a gene that codes for a specific type of chemical that permits retinal cells (cones) to respond to different wavelengths of light.

"All crimsons appear to me to consist largely of dark blue: although several of them seem to have a tinge of dark brown," Dalton wrote, describing his color deficiency. I've seen scarlet, claret, and mud specimens that were almost identical." "A colored medium, possibly some version of blue," Dalton continued, "I think it must be the vitreous humor" (a jelly-like fluid found inside the eyeball itself), "else I apprehend that it might be identified by inspection, which has not been done." In fact, the word for color blindness in French (daltônico), Spanish (daltónico), Italian (daltonico), and Portuguese (daltônico) is derived from his surname. Dalton's eyes were tested after his death and confirmed to be anatomically normal.

Despite being wrong in many ways, this work was the first to publish on color blindness, which is now known as Daltonism in his honor.

Photo: knowyourmeme

Photo: elsevier -

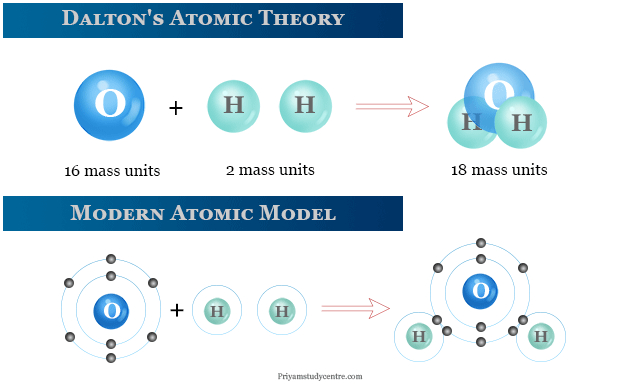

The Atomic Theory was Dalton's most famous contribution to science. Democritus (460–370 B.C.E.), a Greek philosopher, postulated that all substance was made up of tiny particles called atoms, which were invisible to the naked eye.

Dalton disagreed with the widespread belief at the time that all atoms in all kinds of matter were the same. Instead, he proposed that all atoms of a given element were the same, but that atoms of different elements differed in size and mass. He went on to say that more complicated compounds were generated by combining two or more distinct atoms, and that chemical reactions were nothing more than atom rearrangements. He came up with The Law of Multiple Proportions, which states that when atoms join to form compounds, the weight ratio is always a whole number. When a fixed amount of one element is coupled with a second element of uncertain mass, the mass ratios will be small whole numbers as well.

Dalton backed up his hypothesis with experiments, calculating the relative weight of atoms by observing how elements like hydrogen (to which he assigned an arbitrary weight of 1) mixed with fixed proportions of other elements. In a series of articles, he presented his atomic hypothesis to the Manchester society in 1803. He presented his findings in the two-volume book, New System of Chemical Philosophy, after being encouraged by his peers in the organization (part one in 1808 and part two in 1810). Despite issues with his atomic weight measurement, his idea was fundamentally sound and eventually became a part of modern chemistry's foundation.

Photo: priyamstudycentre Source: ChemSurvival youtube channel