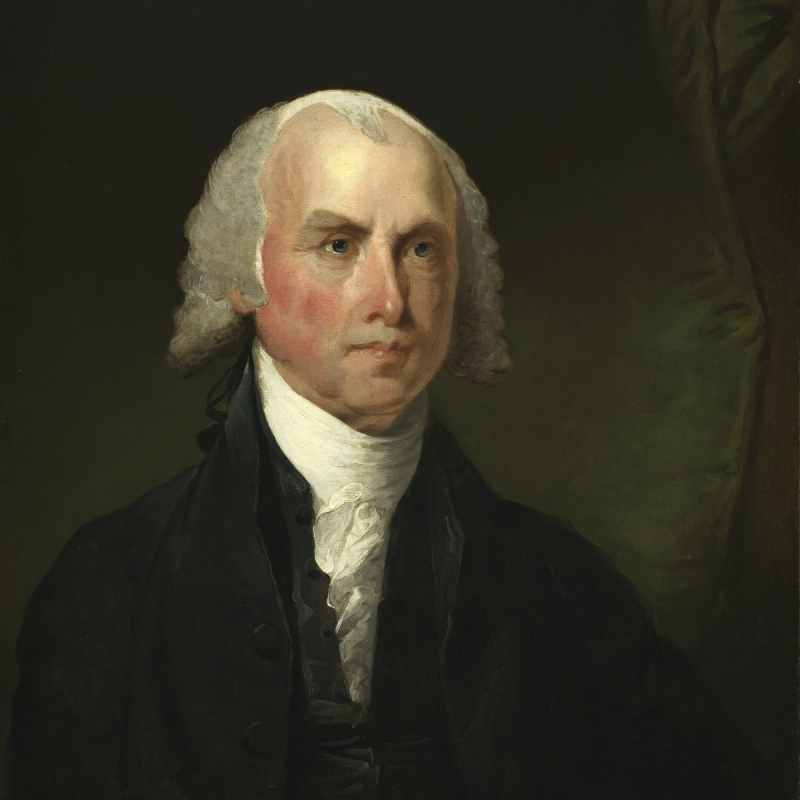

James Madison

The Federalist Papers, co-written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, who served as America's fourth president from 1809 to 1817, significantly aided in the passage of the Constitution. He was referred to as the "Father of the Constitution" in later years.

James Madison, a diminutive, aged man, appeared aged and worn during his inauguration; Washington Irving called him "just a withered little apple-John." But whatever Madison's charm flaws, Dolley, his wife, made up for them with her warmth and joy. She was Washington's talk of the town.

Madison, who was born in 1751, was raised in Orange County, Virginia, and went to Princeton University (then called the College of New Jersey). He was a leader in the Virginia Assembly, a history and government student, and a well-read lawyer who helped draft the Virginia Constitution in 1776. He also served in the Continental Congress.

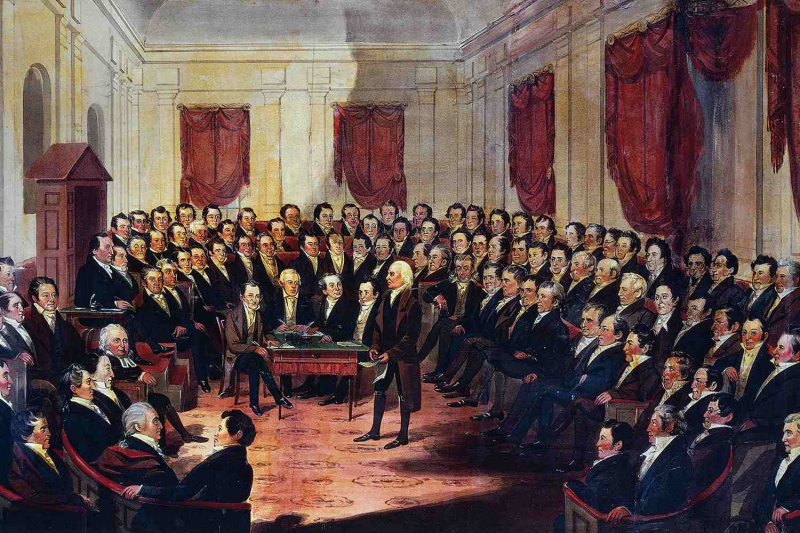

The 36-year-old Madison actively participated in the debates when the participants in the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia.

Madison, along with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton, wrote the Federalist essays, which were a significant factor in the approval of the Constitution. Madison objected when he was later referred to as the "Father of the Constitution," saying that the constitution was "the work of many heads and many hands" rather than "the offspring of a single brain."

He worked in Congress to draft the Bill of Rights and pass the first tax law. The Republican, or Jeffersonian, Party was born out of his leadership in opposition to Hamilton's financial policies, which he believed would unfairly award riches and influence to northern financiers.

Madison protested to warring France and Britain that their seizure of American ships was against international law while serving as President Jefferson's secretary of state. John Randolph remarked angrily that the complaints were equivalent to "a penny pamphlet hurled against eight hundred ships of war."

Madison won the presidency in 1808 despite the unpopular Embargo Act of 1807, which did not force warring nations to modify their ways but did result in a slump in the United States. The Embargo Act had been repealed before he was elected.

During Madison's first year in office, the United States barred trade with both Britain and France; however, in May 1810, Congress legalized trade with both, authorizing the President to refuse trade with the other nation if either would adopt America's notion of neutral rights.

Napoleon pretended to agree. Madison declared non-intercourse with the United Kingdom late in 1810. The "War Hawks," a young group in Congress that included Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, lobbied the President for a more aggressive approach.

The British impressment of American seamen and the seizure of cargoes forced Madison to cave. On June 1, 1812, he requested that Congress declare war.

The nascent nation was unprepared to fight, and its armies were routed. When the British arrived in Washington, they set fire to the White House and the Capitol.

However, a few noteworthy naval and military successes, capped by Gen. Andrew Jackson's victory at New Orleans, persuaded Americans that the War of 1812 had been a resounding success. As a result, there was an increase in nationalism. The New England Federalists who had opposed the war and even discussed secession were so overwhelmingly discredited that Federalism as a national party vanished.

Madison spoke out against the disruptive states' rights pressures that threatened to dissolve the Federal Union in his retirement at Montpelier, his mansion in Orange County, Virginia. "The advise nearest to my heart and deepest in my principles is that the Union of the States is cherished and sustained," he said in a note opened after his death in 1836.