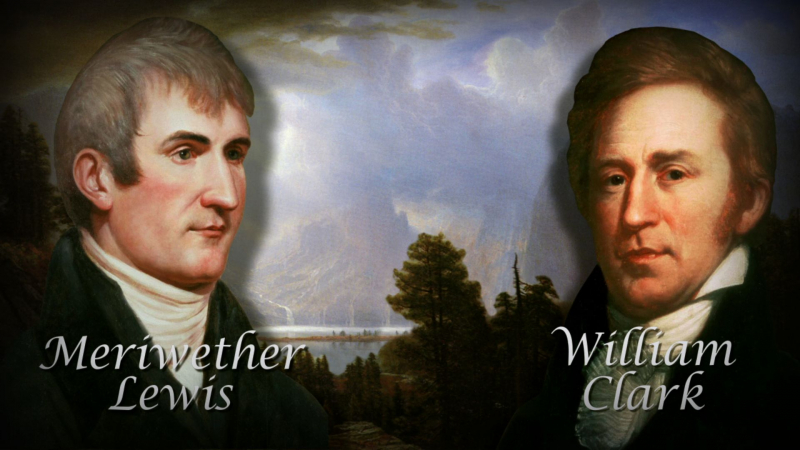

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

William Clark (1774–1809) and Meriwether Lewis (1770-1838) In 1804, Lewis and Clark led an expedition that traveled from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, through the middle of the country (including the recently acquired Louisiana region), and then along the Pacific coast to the west coast of America. Thomas Jefferson ordered the voyage in order to determine the most viable path to the Pacific and, more crucially, to have the American government formally claim the entire landmass on behalf of the United States before competing European countries attempted to do the same. The mission also aimed to learn more about the continent's interior and, at Jefferson's request, improve ties with American Indian tribes. They came back to St. Louis after two years and informed the president of their findings.

William Clark and Meriwether Lewis are still remembered as one of the most well-known duos in American history. However, underlying the legend surrounding their 1804 - 1806 trip and the collaboration that led it, the two men whose names have been inextricably intertwined once again had a friendship. Despite coming from well-known Virginia families, Lewis and Clark did not meet until they were adults. In the 1770s, Clark's family which included his famous Revolutionary War commander brother, George Rogers Clark moved to Kentucky. Lewis and Clark finished their official studies and joined the military. They fought alongside General Anthony Wayne in the same battalion in 1795, where they grew close. Both earned a reputation for being effective commanders and seasoned outdoorsmen, albeit Clark was more skilled at surveying and water navigation than Lewis. Their shared connection to Thomas Jefferson helped them later on. Lewis was appointed as Jefferson's personal secretary after the president's inauguration in 1801. Jefferson approved of Lewis's selection of Clark as co-commander while the Corps of Discovery trip was being planned. Although Clark served as the official second in command, Lewis regarded Clark as his equal, and the two made all decisions together throughout the expedition.

The majority of the expedition's troops were recruited and trained by Clark, while Lewis oversaw the preparation of the expedition's supplies. The expedition left in May 1804, traveled up the Missouri River and camped in the Mandan Indian territory for the winter after five months. Lewis and Clark successfully traversed the Rocky and Bitterroot Mountains with the essential assistance of Native American guides and interpreters, the most prominent of whom was Sacagawea, a Shoshoni woman. They frequently had to trek on foot while utilizing horses they had acquired from indigenous as pack animals due to the difficult terrain. When the group arrived at the Columbia River's tributaries, they constructed boats that would take them to the Columbia River's mouth and the Pacific Ocean. While Clark directed physical operations, supervised physical activities, surveyed mountains and rivers, and attempted to determine navigable routes, Lewis spent a large portion of his time observing the natural world and caring for the men's health. After spending the winter of 1805–1806 in modern-day Oregon, the group set off on their return trip, splitting up along the route to investigate the Continental Divide and the Upper Missouri River. When Lewis and Clark reached St. Louis in September 1806, they got to work writing their diaries, which would help future explorers create a precise topographical map of North America.

The voyage turned out to be the pinnacle of their professional lives. In order to support Lewis while he drafted his documents, Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1807. Lewis had a history of depression and had mismanaged his finances, resulting in debt, which made him even more depressed and inclined to binge drink. Lewis, who was only 35 years old at the time, passed away from a gunshot wound while visiting an inn in central Tennessee in 1809. The majority of the available data supports the conclusion that Lewis committed suicide, despite some researchers' claims to the contrary. In 1807, Clark was appointed director of Indian affairs, and six years later he was chosen to lead the Missouri Territory. After Lewis passed away, Clark took over the responsibility of getting his journals ready for publication. He enlisted the help of banker Nicholas Biddle, who edited the writings for their printing in 1814. Biddle concentrated primarily on the expedition's geographic discoveries, overlooking many of Lewis's meticulous notes on flora and fauna.

Nevertheless, the journals' publication sparked interest in the West due to their descriptions of native tribes and natural resources, which proved to be very helpful to the geologists, surveyors, and anthropologists who followed Lewis and Clark.